Accountable for What?

Oops! Misspelled Buddin's name. Oh, well-- he's probably making enough money on these contracts to buy back the other 'd'.

Recently, I had a chance to catch up with a former colleague of mine after school, in her classroom. As often happens when teachers chat, we tried valiantly not to talk about school, but gave up after about five minutes.

“I just saw that movie, Waiting for ‘Superman’. I’d been so excited about it, thinking that it was such a great opportunity for education to finally going to get the attention it deserves. I left with a stomachache.”

(I’m sure you can picture me nodding in agreement.)

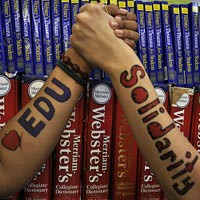

She continued, “It was just so clueless.” I followed her eyes around her classroom, as she glanced over the different areas of her classroom– visually tallying her to-do list, as I often do. “I mean, I’m thinking about all the different things I have to do: send in notes from grade-level meetings and data team meetings, submit my (students’) AR goals to one person, hand in my kids’ reading data for the week to another person, start preparing my grades, do SMART goals for my kids who have ILPs, share my lesson plans with our admins…it goes on and on. Everyone is demanding that I do something different– I feel like nothing that’s going on here is my choice. So how is it fair that teachers get blamed for everything, when I’m not even making any decisions?”

“Exactly,” I said, commiserating. “To hear them tell it, you’re the root of all evil, yet if that guy had even bothered to talk to a teacher in one of the schools he trashed, he’d probably see a lot of hard-working people– a lot of people jumping through hoops to keep up with other people’s demands.”

As the Los Angeles Times continues its crusade publishing teachers’ value-added scores (and misleading the public in general– like most principals and peer teachers never knew who was good and who wasn’t before they came along with their stupid algorithm? Like most teachers never shared their teaching practices? Are they serious?!?!), and as the federal Department of Education continues to justify raising the stakes on standardized tests and teacher evaluation, I keep coming back to the faulty assumptions surrounding teacher accountability.

News flash: It makes no sense to hold people accountable for things they cannot control.

Now, I’m not even just talking about student background characteristics, and poverty, and the other things that are generally considered when statisticians and researchers calculate that around 90% of the variance in students’ scores are the result of “student-level factors not under the control of the teacher.”

I’m talking about the things that go on inside the classroom, that most people assume are completely up to the teacher. Things like decisions about curriculum, how materials are used, how time is used, etc. Increasingly, and especially in “failing” schools trying to comply with district, state and federal mandates, these decisions are made outside of the classroom. Teachers are required to follow strict pacing and planning guides– if not a fully scripted curriculum– whether that pace works for their students or not. Teachers are required to teach certain topics in certain ways, and follow a mandatory schedule (i.e. 90 minutes exactly, uninterrupted, of literacy; 75 minutes exactly of math, etc.). Teachers have to keep up with building, district, and governmental reporting requirements– which takes time and energy away from lesson planning, grading, and meeting with students and parents. In some places, school and district officials have gone so far as to mandate things like the exact format for how things must be presented on each teacher’s dry erase board.

And none of this even touches on the bigger things that are beyond most teachers’ control– the sizes of their classes, whether or not they have in-class help, whether they have the materials they need because of budget cuts, or even how long the school week and year will be.

All of these decisions affect teachers’ ability to teach and students’ ability to learn– yet in many cases, such decisions are not made by teachers. (And if you try to do what you think is right despite those official decisions…well, good luck! Especially if you’re still probationary…) So how is it fair, or even logical, to press for greater “accountability” for teachers?

If student performance declines in a place where budget cuts force a district to move to a four-day school week, does it make sense to hold the teacher “accountable” for losing up to 20% of the instructional year? Should a school that follows whatever scripted reading program comes along with federal “support” be faced with reconstitution or closure when students still struggle to read effectively?

Presumably, the point of these accountability measures is to improve teachers’ (and schools’) performance, or to identify and fix instructional problems. But if the people in question have little control over what they do, how is that useful? (And really, if a school is dutifully following a given curriculum or whatever, and still failing, should the school be forced to clean house, or should the curriculum publisher??)

If the educational buck is going to stop at the teacher level, then teachers should be given all the support and freedom for which we ask. But if everyone over our heads is going to get to determine our every move, or limit the resources we need to work, they should bear the ultimate responsibility for the results.

Trackbacks

- The Best Posts & Articles About The Importance Of Teacher (& Student) Working Conditions | Larry Ferlazzo's Websites of the Day...

- Today’s Collection Of Good School Reform Articles & Posts | Larry Ferlazzo's Websites of the Day...

- A Letter to Arne Duncan « Failing Schools

- A Letter to Arne Duncan :: Sabrina Stevens Shupe

- Whose Best Practices? :: Reclaiming Reform | Education policy of, by & for We the People.

- Rebuilding the Village: What Our Schools, and Our Society, Need Now « Actualités Alternatives « Je veux de l'info

- Rebuilding the Village: What Our Schools, and Our Society, Need Now | The Zeitgeist Movement Australian Chapter

>>90% of the variance in students’ scores are the result of “student-level factors not under the control of the teacher.”

Wow, that directly correlates with my realization recently that children really only spend less than 9% of their lives actually in school.

(from birth to 18, 24 hrs/day, 365 days/year vs grades 1 – 12, 6.5 hrs/day, 180 days/year–8.9% of their live span is in school)

I like to say that until we start caring about the other 91% of their lives as much as we claim to about their school performance, it’s all just demagoguery.

Ryan

I’ve seen documentaries and summits that talk about accountability — mostly of the teacher. The elephant in the room that no one is talking about is THE PARENT. It’s no accident that the demise of our public schools (especially in comparison to other countries like Singapore, Finland, China etc.) parallels the rate of childhood/adult obesity. Parents in America at all socio-economic levels just don’t want to do the hard work of disciplining their kids. Permissive parenting has become the norm. So when Amy Chua (the “Tiger Mom”) talks about disciplining her children, she’s considered abusive. If you made me superintendent of a school district where 100% of the students were from Kenya, China, Germany and India, I guarantee that I’d have the highest test scores, the lowest number of suspensions, and the highest graduation rate. Why? Are those students smarter than American kids? Are they naturally better behaved or more focused? Heck no! The difference is that those students have parents that demand excellence of their kids and don’t put up with excuses. When the kid fails a test, the parents blame themselves, not the teacher. American parents don’t have that attitude. It’s always someone else’s fault. When I lose my house, it’s the bank’s fault. When I lose my job, it’s my bosses fault. When my kid fails a test, it’s the teacher’s fault. I am never to blame. And that, along with all these educational budget cuts at the state level — is the signal of a society sliding backwards.

“Parents in America at all socio-economic levels just don’t want to do the hard work of disciplining their kids. ”

So, if you’re a single parent, or a parent that has to work two jobs just to stay afloat in this economy, how does that correlate with not wanting to do the hard work of disciplining?

to be blunt: not every kids is an angel waiting for his wings

But honestly, after listening to my wife come home from school for 20 years, yes parental commitment matters. In fact, it’s basically the end game before law enforcement. You either care about what your kid does in school and are part of the process, or you admit you cannot control your child and ask for help (which is available, and is better than a criminal record for your child).

Add into the scenario that a lot of these students are children of very young adults, who probably matriculated through this same system. You’re often dealing with young parents (and sometimes older) who have authority issues.

Garnering parental resolve is crucial in teaching.

No where in my post did I mention marital status, so please don’t put meaning into my words that are not there. I’ve seen strong single parents who are involved and set limits on their kids. I’ve seen married couples that set no limits and do not teach the lost art of self discipline. The vast majority of parents fall in the middle but shade towards the permissive side, in my opinion. My wife and I set firm limits on our kids and we stick to them. That’s hard. There are few other people I know that do that. As an example, we don’t have a video game system in our house. We’re the only ones in our community where that’s the case. Permissive parenting is the rule, not the exception, regardless of single or double parents. And that’s a societal problem.

oh, and the main point of your post is dead on.

Public school management is top-down. But the accountability is bottom-up.

Back here in Philly, schools are being reconstituted (and that’s before the budget related layoffs which will just cull staff from the ranks completely) yet administrators are collecting performance bonuses!

I just read the following in a breaking news post on Cathie Black stepping down in NYC:

“Reformers in New York and San Diego and D.C. have pushed top-down, authoritarian and anti-democratic policies ignoring teachers, students, parents, and communities in the process. Black’s appointment – she was a publishing executive with literally no education experience – was simply the latest in a long pattern of arrogance and disdain for democracy, unions, and the long tradition of public education in this country.”

from http://blogs.forbes.com/erikkain/2011/04/07/cathleen-black-steps-down-as-chancellor-of-new-york-schools/

Wow RSR, that is a scoop. I remember reading on an edu-blog shortly after Black’s appointment that they didn’t think Black would last longer than this spring. I wish I remembered who said it- I’d suggest they buy a lottery ticket!

The post exemplifies the workings of the Reformers Laws of Educational Accountability:

First Law: The greater the authority over education, the less the accountability.

Second Law: That for which anyone is accountable trends toward entropy.

Third Law: Responsibility never rises above the level of parents, students, and school level personnel.

Teachers who are let go because they are ‘ineffective’ have to be replaced. Who replaces them? Will the replacements do a better job? Will they last any longer than the person they replaced? Accountability can only be successful if the following statement is true:

1) Teacher labeled ‘ineffective’ actually are ineffective, and there is a pool of candidates who will quickly become more ‘effective’ teachers than the teacher they replaced.

Nobody has convinced me this is true.

Worth reading on VAM and the LA Times…

http://www.fair.org/index.php?page=4270

I just watched “Waiting for Superman” (about 2 hours ago) and I don’t understand why teachers don’t like the documentary. Sure, they do stress the difference between a good teacher and a bad teacher, but they also emphasized that good teachers can’t do what they wish to do because of all the administration requirements. They also emphasized the idea of the lack of choice for schools and the ridiculousness of stopping students from trying out for the best schools unless they’re willing to take risks with charter schools or pay money for a private school. So they definitely don’t fully blame teachers.

I think the main points of “Waiting for superman” were: 1) good teachers can’t do their job well because of all the various administration rules 2) bad teachers are hard to get rid of 3) parents don’t have much power over their kids’ education.

We don’t like it because it’s inaccurate. The movie claims to be about what’s wrong in our educational system, but in two hours spent talking about “failing” schools, they never actually talk to anyone in one. (From a documentary standpoint, that’s just bad. That’s like making a film about Arctic penguins and never leaving Los Angeles.) Guggenheim consults a number of “experts” (mostly non-educators) who have built careers attacking public schools. It would be like if he re-made An Inconvenient Truth and only interviewed climate change deniers paid by ExxonMobil. He presents a lot of misleading statistics and characterizations that are never de-bunked, because he never actually talks to the people who know the most about these schools– the people who work in them everyday. He overstates the difficulty of dismissing ineffective teachers; principals are just required to document why they believe a teacher is ineffective, and give them a certain period of time to improve. (The length of that time varies from place to place).

He also repeatedly makes exaggerated to flat-out false statements, like when he says that “failing schools make failing neighborhoods” and suggests that poverty and race don’t affect student outcomes. They absolutely do– they’re far more highly correlated with standardized test scores than anything else, partly because income gaps breed opportunity gaps (in terms of the opportunities children have in and out of school, and the local resources available to fund schools), and partly because standardized tests and other achievement-related school practices are not culturally neutral. So long as school success is defined in such a narrow way, kids who don’t perform in that specific way, for whatever reason, will be considered “failures” regardless of their intelligence, effort, or growth.

Finally, many of us who are teachers don’t like the film because it insinuates that the largest problem facing schools isn’t intergenerational poverty, or institutional bias, or under-investment, or mis-allocated resources, etc., but teachers who just don’t care enough to do better. If that were the case, that would necessarily mean that there are far more bad teachers out there than we know to be the case. It becomes a personal attack. Our work is incredibly difficult, and the overwhelming majority of us care far more about our work than one would guess from listening to outsiders discuss it. We sacrifice better pay, better working conditions, free time, and quality time spent with our own families in order to do right by our students. But too often, we’re on our own in that regard– we don’t have the institutional and community support we need, and we’re held responsible for things far beyond our control (as this post explains).