The Culture of Fear

One of the hardest things about this project, and about offering any kind of counter-narrative to the “Public schools suck/Teachers are terrible/If only we could [insert gimmick here] our problems would be solved!” party line, is dealing with the culture of fear that exists in so many schools (and other work environments, for that matter!). The culture of fear is what prevents so many teachers from coming forward and talking about their experiences as teachers, and what causes others to do so anonymously or pseudonymously. Because of this, it’s easy for self-styled reformers (you know, the folks who’ve never taught, and may not have ever even attended public schools, but know all the answers to the problems in education) to pretend we’re all lying or exaggerating when we talk about the pitfalls of their pet projects. I’ve come to think of the culture of fear in schools as one of the most public secrets ever– most teachers have experienced it in at least one school, but many people outside of schools either don’t like to admit it exists, or can’t believe that it does.For instance, when I first started having trouble with my administration this year, a lot of my non-teacher friends would say things like, “Well, don’t you have a union? Aren’t they supposed to crush your principal into dust for even looking at you wrong?” From there, a conversation would ensue about how lucky unionized teachers are to be so well-insulated from any kind of accountability, and how in no other profession can you be terrible at your job and keep it for life blah blah blah, and I would tune out and drift to the mental happy place I visit during savasana in order to not go completely nuts.

(I won’t really get into the union thing right now, ’cause that is a can of worms I’m saving for a day when I have a much heartier stomach. For now, I will offer this well-clicked link instead: The Myth of the Powerful Teachers’ Union. Note that I offer it only for the comparative statistics on teacher job security in unionized vs. non-unionized public school systems, and the appropriate call to stop blaming schools for societal problems. There are a few places where I think he’s being really disrespectful to low-income students and communities, and I disavow that completely. Bottom line: Teachers’ unions are not as powerful or protective as people think.)

In well-functioning school environments, there is no culture of fear. Teachers, administrators and parents (and students, wherever possible) trust and listen to each other, respect and value each others’ input, and make decisions based on mutual consent. Students win because the adults in their lives have the energy and resources to do what’s best for them; teachers win because they’re respected as professionals and are free to focus on instruction; administrators win because they can focus on positive management of personnel and resources; and parents win because they can trust that when they send their children to school, they’ll be safe and well-educated.

Unfortunately, too many schools these days don’t fit that description. Districts responding to state and/or federal mandates are increasingly inflexible, and judge schools based on a few easy-to-report measures of performance. Those measures–the all-important Data– may or may not tell anyone much about real learning, but to folks who don’t understand education or see schools or students up close, they’re all that matter. If a school comes up “short” on these measures, then harsh “turnaround” strategies are often employed.

Fear kicks in.

The fear pushes administrators to crack down on those areas that are most visible to the district. If they don’t, they risk losing their own jobs in a turnaround or school closure. They pass the fear along. For teachers, there’s a difficult choice: should you teach to the Test, or to whatever your principal and district value at the moment, or teach to students’ needs, abilities, and interests? Theoretically, those things should not conflict, but when high-stakes assessments can’t be adjusted to suit different learning styles, only account for a narrow range of subjects, and produce information only after a cohort of students have left a given classroom, conflict is inevitable. The fear looms: is it best to go along with the program–“play the game”– even though it’s not real education? Is it worth it to risk a steady salary/your professional standing/your entire career to stand up for what’s right for the kids?

When teachers question anything about the current way of doing things, that poses a problem for administrators. On the one hand, they have a point. On the other hand, no one’s listening to that point, and I can’t do anything about that this year. Do I allow that, or do I shut it down so I can keep the bus rolling until this fad passes? The easier thing to do is to shut it down. Silence those teachers, so others don’t start questioning too. The other teachers witness what happens to someone who doesn’t quietly go along, and they quickly learn to keep their mouths shut. Yeah, this situation is failing the students, but I’ve got a family to support. I’ve worked my whole life for this career. I can’t afford a bad evaluation, or an involuntary transfer, or to get passed over for a promotion, or to lose my job completely. They might gripe in the teacher’s lounge, or blow up at kids for being bad, or lazy, or unmotivated. But they won’t publicly take a stand, because they fear what might happen if they do.

(Note how slippery this is for a teacher’s union. If a teacher gets fired for questioning or resisting district, state, or federal policy, there’s not much they can do to protect that teacher. If “doing your job” means going along with the policy, then that teacher was not doing his or her job; there’s really no official recourse for that teacher. The only way to keep good teachers in the system (and support them to do real teaching) is to work to change the policy. Of course, if the flawed policy is touted as a much-needed “reform,” how can you resist it without also appearing to be against reform?)

So, as a teacher, you’re on your own. Work becomes about keeping up your guard. Can I trust my teammate enough to share my real feelings about how things are going? Should I admit that I’m struggling with something– class size, lack of materials, a new curriculum, forms and reporting requirements– and ask for help, and risk being seen as incompetent, or a complainer? Should I talk to outsiders about what’s going on, and risk a superior finding out about it and retaliating against me?

Which school would you rather send your children to: the one where people work together and teachers can spend their time focusing on their actual work, or the one where administrators and teachers don’t trust each other, and don’t do what they think is best for students because they’re all afraid they’ll lose their jobs?

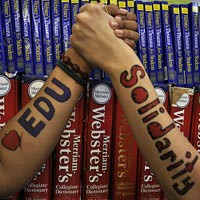

The good news about this situation is that it’s fixable. Cultures develop as people respond to the circumstances they face, and we have the power to change our responses and those circumstances. The bad news is, that means we need to be brave enough to make those changes. Teachers need to come together and speak out against abuses in the system, and reclaim our expertise in the education reform arena. If the public is going to become informed enough to resist well-intentioned but short-sighted (and thus, potentially harmful) plans to “fix” public education, we are the only ones who can inform them. Likewise, administrators need to be brave enough to foster cultures of openness and respect, and take their employees’ concerns seriously. Districts need to hold everyone–teachers, administrators, and themselves– accountable for behaving professionally, which includes addressing well-founded dissent instead of suppressing it.

“I said, ‘Somebody should do something about that.’ Then I realized I am somebody.” -Lily Tomlin

I think one very inportant point you made was that the visible parts get all the attention. Its like trying to cure skin cancer by covering it up with a long sleeve shirt. DC may be the worst place for this because of the hyper-political atmosphere but we need more teachers and admins willing to cut through the bullshit. I don’t think that anyone is against positive results but many of us are against papermache results that are hiding the cavity which is growing because we’re ignoring it.