Social Promotion vs. Retention: What do you think?

This question came up in the comments on our last post, on Twitter, and elsewhere. It’s a tough one, and the research appears mixed (though I’m not as well-versed on this as I’d like to be– if you have a better handle on it, please weigh in!).

This question came up in the comments on our last post, on Twitter, and elsewhere. It’s a tough one, and the research appears mixed (though I’m not as well-versed on this as I’d like to be– if you have a better handle on it, please weigh in!).

On the one hand, there is a strong relationship between retention and poor student outcomes (persistent low performance, dropping out, etc.). On the other hand, the idea of moving students forward when they haven’t mastered the skills we’ve decided they need in the next grade seems counterintuitive. Aren’t we just setting them up for failure?

On some other crazy third hand (or foot? Can we use our feet when there are more than two sides to a story? ;)), isn’t this an unavoidable problem when our whole system revolves around how old students are, rather than what they know and can do? (Is that the problem we should be addressing, instead of batting this one back and forth?) Or to add a fourth limb– is it reasonable to have such rigid expectations of what students will be able to do in a specific, usually very small, time frame? And is it fair when we ask so much more of kids today, at a younger age, than what was expected of students in prior generations? (I still have all the binders I stuffed with the 5th grade standards for literacy and math alone, and standing vertically as they do on my shelf, they’re wider than I am. That’s a lot for a ten-year-old…)

One other piece: what about the social and emotional considerations that weigh on this decision? Emotional states affect cognition, and negative emotions make thinking and learning much harder. Though it gets left out of the discussion these days when we focus more heavily on strict measures of achievement, one key assumption (typically correct) that favors social promotion is that it is demoralizing and stigmatizing for low-performing students to be “left behind” their peers. However, I’d imagine it’s also pretty demoralizing and overwhelming to feel behind all the time, too. And even when I think about alternatives where students advance through different levels based on their mastery of the standards rather than advancing strictly by age, I still imagine that the same stigma that applies to being held back a grade may affect those students who don’t move through the levels as quickly as others. (This is currently being tried in the Adams 50 school district here in Colorado; can any teachers or observers there talk about how that’s being handled? What kinds of school culture or community-building efforts, if any, have been implemented alongside these reforms?)

One other piece: what about the social and emotional considerations that weigh on this decision? Emotional states affect cognition, and negative emotions make thinking and learning much harder. Though it gets left out of the discussion these days when we focus more heavily on strict measures of achievement, one key assumption (typically correct) that favors social promotion is that it is demoralizing and stigmatizing for low-performing students to be “left behind” their peers. However, I’d imagine it’s also pretty demoralizing and overwhelming to feel behind all the time, too. And even when I think about alternatives where students advance through different levels based on their mastery of the standards rather than advancing strictly by age, I still imagine that the same stigma that applies to being held back a grade may affect those students who don’t move through the levels as quickly as others. (This is currently being tried in the Adams 50 school district here in Colorado; can any teachers or observers there talk about how that’s being handled? What kinds of school culture or community-building efforts, if any, have been implemented alongside these reforms?)

What do you think? Bring your opinions, experiences and research citations in the comments!

There is a huge amount of research showing that holding back kids hurts rather than helps them, esp. in the long run. Check out the letter from experts, opposing this practice at http://www.classsizematters.org/retentionletter.html

signed by over 100 academics, heads of organizations, and experts on testing from throughout the nation.

Among the letter’s signers were four past presidents of the American Education Research Association, as well as three members and the study director of the National Academy of Sciences Committee on the Appropriate Use of Educational Testing, and two members of the Board on Testing and Assessment of the National Research Council.

Thanks for always being on top of the research, Leonie! You rock.

The class size connection also reminds me that a lot of these issues– related to achievement, social & emotional development– are improved in smaller classes. We could probably put much of this discussion to rest if we committed to creating environments where kids could get the kind of small group & individual attention they need as often as they need it.

Your link is not working. Just what do they base their research on other than the age of the students? I believe, done correctly, holding kids back is the best thing that can be done (I have did it with both of my sons and they are thriving). The other thing is we need to move away from “age” as a criteria in education. As more and more urban schools become heavier and heavier with FARM kids the concepts of grades and age needs to go away.

Do these researchers who oppose retention have an alternative for moving students from grade to grade without mastering knowledge and skills? So for 15 years we let children ‘feel good about themselves,’ then they reach high school, social promotion stops, they don’t earn credits timely, and they drop out. What’s the solution?

Teachers & schools have assessed students poorly, contributes to executing retention poorly. All schools may not be thorough in providing students every opportunity to master the required knowledge and skills. The goal MUST be students mastering knowledge and skills before being challenged with more complex knowledge and skills.

As for these ‘academics’ and ‘experts on testing,’ how many of them have been in the classroom with students who’ve been socially promoted? Urban high schools have been ‘drop out factories’ simply from having so many young people, for example, who can’t multiply past their 6’s with any fluency dropped into an Algebra 1 class that they cannot pass in 1, 2, or even 3 attempts. The next time someone says to me ‘research-based,’ they better put the ‘research’ in my hand so as to asses it myself. Even gamers understand you can’t get to level 2 in a game until you passed level 1; how shameful that such common sense rarely applies to public education.

“One more thing….”

Reading that letter against retention only supports my statement about poorly executed retention programs. Relying primarily on test scores is as inept as relying primarily on test scores to evaluate teachers. Retention requires the type of collaboration required by an Individual Education Plan (IEP), at least. Of course you’d need multiple measures of a student’s lack of achievement and growth to make that decision, and even then the final decision should be the parents.’

Well said. We held back our boys not due to academics but because they needed additional time to mature. Had I listened to my father they would have started kindergarten when they were 6. My father really did know best. My son’s are in college and are thriving. Maybe if there is such strong resistance to holding kids back the cut off date for being eligible for school needs to change – push it back 6 months or more in particular for boys. Just a thought.

As a long time K teacher– I have to disagree that retention is inherently bad.

If kids are young (k-1), immature emotionally, socially, academically, have a late birthday AND

THE FAMILY IS SUPPORTIVE, then it can be a very successful intervention.

I have seen many children who were retained under these circumstances blossom and were great students in all areas by 5th grade or before. Time can help kids, especially kids who were not given the best experiences before they came to K. One of my kids who was retained in 2nd grade is on track to graduate as an anesthesiologist.

Kids who did not attend preschool, have never held a book, pencil, crayons or scissors, have never had conversations, nor were expected to respond to others verbally, do not stand a chance in a K classroom where most others have had these experiences. Combine that with a stubborn, willful personality and a summer birthday and in my class of 24 (down from my usual 28), this child will have a hard time mastering the Kindergarten expectations.

I fully agree that we are pushing ALL of our students in the wrong direction. But since I am not listened to as a teacher/educator by those in power, by myself I am not able to change things at the institutional level. I really feel that many more parents need to step up and disagree with the way education policy is traveling in America, before we fall off the cliff. Human and brain development has not advanced enough in the last 50 years for us to be pushing our children this way.

I also speak as a parent on the pluses of retention; although mine were preemptive, both of my kids have summer birthdays, and could have started K at 5. I chose to keep them in preschool for another year and send them to K when they were 6. This has nothing to do with how smart they are. (retention does not, or should not address smartness–) You could be Einstein, but if you can’t listen to a story for 5 minutes you are not going to be able to demonstrate that greatness. The gift of time and the natural maturing that happens with time can allow that child to tap their greatness.

In my children’s case, one child was diagnosed with dyslexia in fall of 1st grade (at 7 yrs old), and the other child wasn’t interested in schooling, type work/play. Both were not ready to start at 5.

Both will turn out fine– as long as they don’t drive me crazy first. 🙂

I mostly agree. I retained a student last year with a late November birthday. Despite a lot of interest and obvious intelligence and creativity, he wasn’t ready for first grade. His fine-motor skills were very low and (and I type this knowing it is anathema to legions of reformers) he was not physically or developmentally ready to read with understanding and pleasure. So after a lot of discussion, input and a review of Light’s Retention Scale (not to score him, but to guide our thoughts), we retained him. He’s doing very well.

Even so, this involved a lot of class meetings and discussion with his now first grade peers.

However, I worry sometimes that some kids who come to Kindergarten without preschool experience get written off early, and that we miss other students who did have preschool but still aren’t ready developmentally. Again, it’s all that brain research: there’s a big range in child development and our system is not equipped to take that seriously.

I remember reading that children will be ready to read between the ages of three and eight, for instance. Yet what I head from education officials is that everyone will read in Kindergarten and on grade-level by the end of third, and if they don’t it is the product of bad teaching and bad parenting. Our expectations weren’t high enough, there weren’t enough books in the home, etc. The possibility that every child is brilliant but different isn’t something they want to touch.

Totally agree about where administration and policy is heading us.

This is the big problem– none of these new standards/expectations have been examined from a brain/development perspective. Evolution just isn’t that fast.

Scientists need to get on this right away– we are going to lose an entire generation of children, who never could possibly be good enough, because the bar continually moves up (100% of kids at standard by 2013– what idiot thought that would be possible now that they want Kindergartners to read?).

My Resource room teacher already can’t spend enough time with each kid and is seeing that the older kids are giving up. There is way too much assessment, and all it tells us is that kids can’t make the standard and are very frustrated.

If they are so devastated by 5th grade what chance to we have to get them through HS??

Thanks for the comments, everyone! Great points.

@Kristina, re: “Human and brain development has not advanced enough in the last 50 years for us to be pushing our children this way.”

Yes, yes, a MILLION TIMES yes! Such an important point. I think we forget that just because we can collect, analyze, and disseminate Data quicker than you can say “Another TEST? RLY?”, it doesn’t mean kids’ brains are any faster at doing difficult things like learning how to read. When we take all this information, (misinterpret it half the time…) and then cluck and crow because “OMIGOD it’s the second month of third grade and Jimmy’s reading like its the last month of second grade!”, then flood kids with interventions when they should be at recess, we’re most likely making things worse instead of better.

I can’t count how many times I’ve sat in Data Team meetings, wanting to laugh out loud (or cry) at adult hand-wringing over kids not doing things in first grade those very teachers never had to do until third or fourth. And somehow, they survived.

I would LOVE to hear from some brain development researchers, in the public media, about this educational push and how it won’t make our students better people.

And how it takes THOUSANDS of years for evolution to happen in complicated systems (okay, thousands may be an exaggeration).

LET’S SEE THE DATA!!!

Yes, that was total sarcasm coming from a teacher tired of all of the assessment (most in K is done 1 on 1) that takes away from learning time.

I’m one of those who believes children’s progress in learning shouldn’t be tied to age-based grade levels. I’ve raised 11 children myself, and they each developed and learned differently; multiply that by the hundreds I’ve taught, and you get an idea of my database (I’ve studied the research as well). Not only is it possible for a child to be at one level in math and another in language arts, but I’ve also seen children fluctuate or spiral in their development in a particular area, especially writing, as they stretch and try new things. These fluctuations are normal and would result in significant and lasting intellectual growth, if we wouldn’t stunt the learning processes by forcing them into arbitrary grade level molds. Attaching standardized testing to each grade level actually worsens the problem, creating more unnecesary choices between retention and social promotion. One of my hopes for the future of education in US is that we will move towards more individualized instruction, especially now that we have the tools to do it.

This is silly. The only reason social promotion exists is because the “grade” system exists. Passing from 6th to 7th grade is not an achievement. Being able to calculate the slope of a line is. Eliminate “grades” (not A, B, C) and stop associating age with skills and knowledge. Our whole system is based on age discrimination.

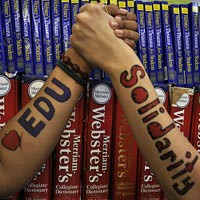

Renee and Patrick have got this right. “Social promotion” wouldn’t exist if we were tracking individual kids’ learning instead of being focused on batching and comparing kids in same-age groups. The problem isn’t social promotion or the efficacy of “holding back” a student (think about the deeper meaning of that phrase–which is, admittedly, kinder than “failing” or “flunking”). It’s with the way we have the system set up. And–we can do something about that.

Most critics of social promotion have punishment in mind–there’s a kind of mean-spirited competitiveness under the idea of standardizing learning.

Like Emerson Junior High, which I attended in Pomona, CA, I worked at two juniors highs which were 7-9. At Letha Raney in Corona, CA, I didn’t notice a problem about retention (was still getting my feet wet and you don’t notice all around you). But at Edison Junior High (now Middle School) in LAUSD, a counselor explained when we had certain… problem children. The problem was most noticable in the 9th grade: a problem student, aged 16, able to drive his own car to junior high.

That’s just a symptom, because I began to notice that those who had been retained were not just headed down a road to dropping out–they started to become predators towards the kids in their new grade level. Older, bigger, more bitter. In those instances, we had more than one counselor willing to simply transfer the kid up to Fremont High–which was, essentially throwing the problem over the fence into the neighbor’s yard. It didn’t solve the kid’s problem; it protected other students. Yet the message it sends the kids is “Go ahead, flunk everything in K-8, because you’ll be taking classes with your friends next year anyway.”

Upon entering the 9th grade in high school now, credits count, but 8 years of conditioning have taught the students otherwise. Many flunk classes in the 9th grade, end up taking 10th grade classes the next year (I know, I’ve taught mostly 10th grade for better than 16 years), but it doesn’t really hit home until a couselor starts talking graduation requirements at the end of the first semester in 10th grade. By then, the hole has been dug.

It also doesn’t help when certain subjects are “self-contained,” with bulkheads and hatches like a submarine. Flunk 10th grade World History, then move on to 11th grade U.S. Flunk that, move on to 12th grade Government and Economics. An F in one doesn’t preclude an A in another. English classes have similar stories. But when you get into Math and the Sciences, then problems start to become more obvious.

The principals at my current school are horrified; they’ve seen the 15-week grades and are stunned at the number of Fs and Ds. “Why are there so many? Can’t we have a grade recovery program?” The culture of learning has to undergo a shift. I just heard administrators freak out over the number of Fs. At my old school, which has been reconstituted, all current teachers MUST EXPLAIN IN WRITING FOR EACH INDIVIDUAL F THEY GIVE WHAT THEY DID TO STOP THE FAILURE.

I don’t have an answer, but I’ve seen administrators strongly suggest changing grading scales in order to show more students have “demonstrated mastery of a standard.” That is a false solution, but I wish I had one that would satisfy me.

If I recall correctly, Richard Rothstein says in THE WAY WE WERE? that the research findings on the so-called ‘social promotion’ issue are mixed, leaving it unclear that it’s either clearly helpful or clearly harmful. Rothstein is a very thorough scholar of research and I trust his reading on such issues. His point was that those who decry social promotion seem to think it’s yet another newfangled idea to destroy the high-quality education from aGolden Age (usually that never actually existed as recalled, if at all). On my view, much of the objection to social promotion is racist and classist, but I don’t necessarily think that pushing kids along when they are clearly not vaguely close to being able to handle the upcoming year’s schoolwork is a mixed blessing at best for many kids, and if students wind up in high school without being able to do the work needed to graduate, I think there are some serious social and ethical questions we have to address with clear heads and open minds (lots of luck!).

thanks for this starting this conversation, sabrina.

one of my sisters and i repeated a year of upper primary school (her in year 4 and me in year 6) due to school transfers rather than academic performance or social competence among our peers.

in my case, my parents enrolled me in a newly established school which didn’t have a year 7 for me to go into so i was forced to do year 6 again. as a result, i went from being an average age to being ‘old’ for my year. in my sister’s case, we had moved to a state where the ‘birthday cut-off’ was 6 months earlier, so she went from being an average age to being too ‘young’ for her year and was thus forced to repeat year 4. in neither case was our grade retention strategic or voluntary.

while i think we were lucky that we didn’t repeat a year in secondary school, i note that the research consensus is to recommend grade retention in lower primary – if at all. i consider grade retention problematic if it is employed, as it was in our case, for non-academic reasons. at the time, my sister and i struggled to accept why we were being held back given that we were both good students and socially well-adjusted, albeit as mobile students in new locations, schools and peer groups. we both expressed frustration at having to cover material at which we were already proficient. in hindsight, we both would have preferred to progress with our peers – socially and academically.

our situation was further complicated by each of us transferring schools for non-promotional reasons 4 times across 3 states and 2 countries. the first 3 of these transfers were reactive and involuntary, following interstate residential relocations forced by a parent’s employment. the 4th and final transfer for each of us was strategic and voluntary. there was no liaison between schools leading up to or following any of these transfers or surrounding our grade retention.

i also missed two separate terms of school due to interstate and international residential relocations arising from this same parent’s employment. my sister only missed the latter of these school terms but by virtue of her age during our international residential relocation missed a pre-school term – the one immediately preceeding her transition to kindergarten when children are oriented to ‘big school’.

fortunately, our youngest sister (my junior by a decade) had a simpler progression through her schooling. she attended 3 schools in a single state, twice voluntarily transferring for strategic non-promotional reasons and not missing any school terms or being retained in any grades.

grade retention due to student mobility or school transfer (rather than school transfer as a remedial alternative to grade retention) is a relatively unexplored phenomena and i would be interested to hear from those with similar experiences and also researchers who have investigated the social and academic impacts on children. an example of an american study can be found at while an example of australian research is at .

sorry – the links for the studies i was referring to didn’t embed, so here they are sans-html:

an example of an american study is stanford university’s center for education policy analysis 2011 exploration of the effects of student mobility in milwaukee. australian research includes a 2002 report on student mobility, which was commissioned by the department of education, science and training and the department of defence.