Pet “Grieves”: What good teachers worry about

One of my all-time least favorite school reform questions is “If you’re a good teacher, what do you have to worry about?” Without fail, when I or anyone else mentions our discomfort with getting rid of due process, or with weakening unions, etc., someone always asks this question. I understand that not everyone has experience working within school systems (especially unethical ones), and so it seems illogical that reforms intended to improve accountability, etc. should bother those of us who have done nothing wrong.

But the “nothing to hide, nothing to fear” myth is just as false in education as it is in other aspects of life. There’s a reason why we have a justice system that includes due process before the law, predicated on the presumption of innocence: being innocent doesn’t mean you will never face inaccurate, unfair, or unethical behavior.

So, in an attempt to start laying these kinds of comments to rest, I give you the “Pet Grieves” series. These are the kinds of situations that illustrate why teachers feel so nervous about folks trying to take away our rights. Those of us who behave professionally and responsibly are not interested in creating a situation where we can safely get away with chatting on Facebook during the school day. Rather, we know all too well the kinds of sticky situations school personnel find themselves in, that can lead to the loss or dismissal of great educators. The public needs to know them too, so that they can make informed decisions about just what–and whom— they’re willing to sacrifice in the name of “reform.”

Pet Grieve #1: Being asked to lie

Journalist Pamela Kripke is spending the year as a teacher, and blogging about it on the Huffington Post. Recently, she shared the story of her first (apparently ongoing) grievance, occasioned by an administrator who retaliates against her when she refuses to change students’ grades from failing to passing (smells like something that might have happened in DC recently…).

The day after I submit grades for the first marking period of the year, I get a visit from the assistant principal. She walks into my classroom carrying a huge stack of forms.

“You’re going to have to change all of the failing grades to passing,” she says, slapping the papers on my desk.

Dallas Independent School District, Grade Correction Form, the heading reads.

“What?” I ask.

“You’re going to have to change the grades. Too many failed.”

I had heard that kids were promoted without proper skills, but I hadn’t expected to see the sham up close, and so soon. I hadn’t expected to be ordered to participate in it…

Soon after I arrived on campus, I was instructed to give a test worth 15 percent of the grade and a project worth 20. I could not give a test after just two and a half weeks. It would take the students, seventh-graders, about six to settle down. I suggest some other means of evaluation, or even no evaluation. It was not the kids’ fault that six people taught the class during those first six weeks. They could have figured a rabbit would show up next. No, I am told firmly, I will have to give the test and project.

I teach what I can. I write a test. It’s pretty easy, and I prepare the kids for it for days. Three-quarters of them fail.

The project is something the department head creates, and the rest of us have to duplicate it. Write about someone who is important in your life and draw pictures, paste photographs, show and tell. I pare the assignment down to one paragraph, and one photo, if at all possible. I notice that there are packages of colored construction paper and markers in a cabinet, so I hand them out. I devote two days of class to the very important project. Of my 64 students, 14 turn in the assignment. I give the students three extra days to complete it, right up to the minute that grades are due in the computer. I get 14, that’s it.

“Ms. Johnson,” I say, outraged. “I gave the required assignments, and they failed.”

“It doesn’t matter. When in doubt, just give them the 70. It’s so much easier,” she says, smiling. “Here are the forms. Get them to me by Friday.”

I hear from loads of teachers who are pressured to change grades, against their better judgment. Whether it’s a principal who is concerned about the appearance of too much failure, or a powerful parent who wants to make sure their little darling (who’s more interested in snowboarding and video games than Algebra) can get into Harvard, teachers are frequently asked to give grades students haven’t truly earned.

As this principal notes, yes, it is easier to go along with the sham– it spares her the difficulty of explaining high failure rates to her superiors, who probably aren’t interested in hearing about the string of substitutes students have endured, or the poverty of their home lives, etc. (“No excuses,” they say…) Too many teachers will eventually bend to this kind of pressure, because they’d rather do the slightly unethical thing than risk losing certain privileges (promotions, better materials, etc.) or receive a retaliatory negative evaluation (or a non-renewal, if they’re still probationary). It’s also very easy to justify it– “Well, this isn’t perfect, but at least I’m still here for my students…”

But how does it serve students for the adults in their lives to pretend they’ve earned things they really haven’t? After all, will their future bosses tolerate them not doing their work, and just pretend they did something they didn’t? Will their future spouses or children accept them shrugging off their responsibilities? Probably not. School is supposed to help students in the rest of their lives, which means in addition to academics, they’re supposed to be developing productive traits and habits–like responsibility, time management, and so forth. Ideally, a good teacher would not sacrifice such lessons (or dilute the credibility of all grades) for the appearance of success, or to appease more powerful people.

But we’re asked to anyway. And when that happens, it’s important to be able to appeal to some kind of process in order to defend ourselves, our livelihoods, and our students.

This is a worthwhile “Pet Grieve” to start with, as we know these types of situations are anything but rare. I feel like this “Pet Grieve” series is going to be productive and informative. Thanks Sabrina!

This is an accurate summary at what happens to often in the classroom but what is the resolution? What is the process to defend ourselves? I think education in the United States needs a complete overhaul! We need progressive leaders to start the change.

One, there’s the grievance process. Not perfect; in many places (as this journalist found out firsthand), the deck is stacked in the district’s favor. But there is the possibility of getting justice (or at least beginning the process of documenting issues/harms should things need to go to court).

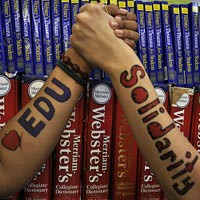

Two, there’s good old fashioned organizing– whether through an official union, or just by establishing unity within the building. Teachers need to stick together (going it alone is professional suicide, as I learned firsthand!) and stop putting up with nonsense because “it’s just so much easier.” We need to start confronting issues honestly, instead of trying to play coy little “nice-girl” political games with unethical/lazy superiors, or society at large. It’s not easier to go along with the wrong thing– it just delays the problem! And problems almost ALWAYS get bigger when they’re put off until later.

I really resent the smug, ignorance of that sentiment. “good teachers have nothing to worry about”. Actually, good teachers have plenty to worry about, especially when we have so many uninformed leaders and policy-makers who are not experts in the field of education.

The example you gave is especially disturbing because the administrator prevented the teacher from fulfilling her primary role which I believe is to advocate for each and every student and that includes making sure they have every opportunity to learn and letting them earn failing grades when they do not take advantage of those opportunities. This requires being honest and knowing each student as an individual and working to provide them what they need. That will sometimes run you into administrators, good or bad, who will not have the information you have or who simply have other agendas. Even in my school where we are lucky to have caring supportive administrators who are on the same page as the faculty we have times when teachers really need to be able to speak up in order to advocate for their students. To me this is the essence of what due process is all about and from my own experience I have seen that when teachers speak up for their students it is invariably the older teachers on professional contract who do so while the younger teachers with no “tenure” sit silent. That is changing here in Fla with SB736 which will silence the natural advocates for children in our public schools.

I agree that this is unforgivable behavior on the part of the administrator. Our educational system does need a major overhaul. Students aren’t motivated and it seems grades are the only focus. The fabric of our country will continue to unravel until we become a third world country if we don’t change this now. Relevant education is essential to progress in the right direction. I do have a question for Sabrina. How much support did you solicit from parents and administrators? Have you since learned enough about the students to know what motivates them? What is the layout of the classroom? Have you tried re-arranging the desks to make the students interact in a positive way? Do you walk around the classroom or sit at your desk? Is everyone on the correct reading level for the class? I am hoping that through dialogue, our system will eventually change as teachers discover what the students of today need in order to be successful. This need will never be met unless teachers take a stand for positive change in our schools. All the best to you.

Thanks for the comment. Yes– my philosophy on teaching & learning is student-centered, proceeds from their interests & needs, and is based on interaction and collaboration (Check out this post over at Cooperative Catalyst for a glimpse at my style– http://coopcatalyst.wordpress.com/2010/10/22/dont-hate-collaborate-or-having-fun-while-doing-serious-learning/ ).

I found that many of my fellow teachers shared these ideas, but we differed in our willingness to challenge structures in the school/system that pressured us to do the opposite of what we’d been taught in our pre-service learning and professional development. I ultimately decided to put best practice first, and institutional convenience second. I lost that battle (https://failingschools.wordpress.com/2010/06/25/my-story-part-ii/) but I don’t regret it. I still have faith that, if more teachers and parents stand up for what’s right, we’ll win in the end.

My classroom was never arranged in rows (except for the two weeks of standardized testing, ugh!), and I was never at my desk until after school. Our library was leveled and sorted by genre, and I conferred with students regularly to ensure that they were checking out “just right reading” books and that they were understanding what they read. They also knew multiple ways to select books for themselves, a skill I went out of my way to teach because the students had grown too accustomed to searching solely based on their AR levels (which wouldn’t be all that useful in the real world of a bookstore or non-school library!)

You’re totally right– we will unravel if we continue acting as many of our short-sighted leaders would like. Doing the kind of teaching we both agree on is difficult these days, because top-down mandates encourage gaming the system (as exemplified by this administrator) and standardization, which actually rewards (in the short-term, at least) the un-engaging, sit-in-rows-stare-ahead-repeat-after-teacher style that has been shown to fail.

Yeah…I still remember being accused of all kinds of things and even though I was innocent, it became a game for admin and some of the parents and kids. Complain then wait for the meeting. So glad I left the dysfunction.